One of the ongoing themes of this blog will be that we must learn to question premises if we are going to be a truly thinking culture. We often argue political and religious subjects based on terms given to us... but these very terms are very often problematic at the least. If I ask, for instance, which is the best tasting meat of all, steak or chicken, you may challenge the terms by stating that there are many other types of meat which one might consider "best."

In politics, one of the key terms that always seems to pique my interest is the word "extreme." We are often asked asked to debate - and more often told - whether particular politicians or political opinions or movements are "extreme." The problem is, something can only be considered extreme left or right depending on where your political "center" is.

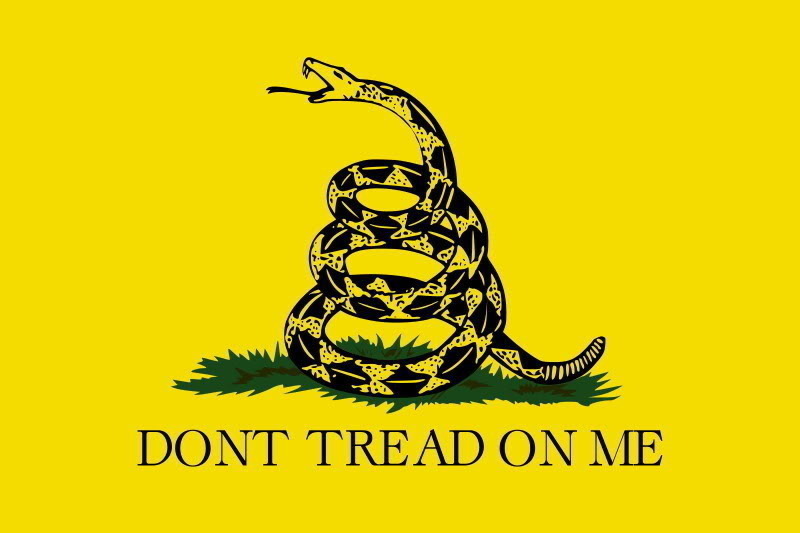

Take, for example, the Tea Party. The Tea Party movement has been based more than anything upon the themes and beliefs of the Founding Fathers of this country. Though certain Tea Party adherents have deviated with their own ideas here and there, the main thrust of the movement has been for lower taxes, smaller government, greater State, local, and individual liberties, a move toward greater personal responsibility, and the preference of local charities and social apparatuses over government welfare. None of these would have been challenged by any of the Founding Fathers. They are the very principles of the Constitution of this country, either directly or indirectly. And yet, the movement was labelled as "extreme" throughout the media. How can this be? To the Tea Party members, their views were "middle of the road." They weren't unreasonable in any way. Their vision of the political spectrum could be seen as such:

<Left (large fed gov't) -------- Center (Federalism w/ limtd centrl gov't) -------- Right (libertarianism) >

For the Tea Party activist, extreme right would be libertarianism or (further to the right) anarchy, or lack of any governing body. This is a fairly simple diagram also of how the Founding Fathers viewed their political views. The Articles of Confederation were a bit too far to the right; the Constitution created a Republic that fit properly and comfortably in the middle of the spectrum. For the media, however, (and most Americans today) their center has shifted very far to the left. Their spectrum would look more like this:

<Left (Communism) -------- Center (Large federal gov't / semi-Socialism) ----- Right (Federalism) >

Thus, when someone claims political "extremism," more often than not this is telling you more about their politics than their subject's. The term, in fact, is mostly used to discredit a position so that one does not have to engage it... It keeps one from being exposed to the criticisms of one's opponents. It is amazing how, with the phenomenon of the Tea Party, very few made the point that the vast majority of the charges of "extremism" could have been equally levied against the Founders of the country, for they were proposing identical positions.

Interestingly enough, this same sort of thinking could be applied to the theology of the Church. Today, so many modern theologian challenge "extremism" of ultra-conservative Orthodox Christians (I don't like the use of the terms "conservative" and "liberal" in speaking of Orthodox theology, but for ease of use, they will be utilized here). There are, to be sure, some whose positions as "defenders of Orthodoxy" are indeed extreme... But when the path that is represented by the vast majority of the Saints is deemed "too conservative," this shows that the spectrum being taken for granted is the real problem. The Fathers always took the "royal, middle path," neither being too loose nor too strict. As such, they ought to be placed at the center of our theological spectrum, with the mind of the Fathers being viewed neither as too "liberal" nor too "conservative." If they fall off to either side of our theological thought, then we know we have a problem either with our understanding of their thought or with our own theological spectrum.

If we are to speak of a "center," either politically or theologically, and extremes at either side, we first must recognize that our "center" is relative. There are, after all, many political commentators, philosophers, and theologians who would consider my views "extreme." For me, this is not a problem; if some such figures considered me "middle of the road," only then would I start to worry...

No comments:

Post a Comment